This unassuming dwarf quince can steal your heart. There are many who have gone to Japan for the spectacular pines, junipers, and maples, only to discover the quiet but memorable Chojubai. Those ‘many’ included a few friends of mine, and myself. This post is a little longer than most because Chojubai is so little known in the West, and, frankly, I think it deserves better. Also, waiting for you at at the end of this long post is a question…

Chaenomeles japonica ‘Chojubai’ is a cultivar of the comparatively coarse Japanese flowering quince. Few plants for bonsai can match its contrasting qualities: Idiosyncratic, craggy branching and twigging, with rough older bark, adorned almost contradictorily with glowing ruby flowers. They flower mostly when out of leaf, in winter, so they lend a feeling of glowing life to the bonsai yard when all else is dull. The details are small, with glossy leaves about 1/2″ long and flowers under 1″ wide. There are several flower variations including white and red, although almost all Chojubai used for bonsai are red-flowered because that variety has the finest twigging.

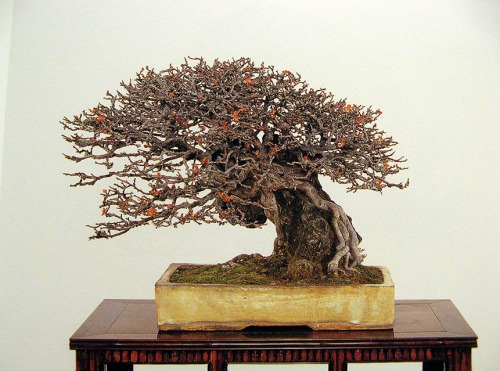

The history of this tree in Japan is interesting… At first, Chojubai appeared commonly as a small accent plant in the Kokufu show forty years ago, as an unramified twig or two. Only rarely was it seen as a primary tree in the medium size category, and never in the large size. It was a second tier tree. Then something shifted. Around 1990 we began to see large size Chojubai in the Japanese shows. These were trees about 1-1.5 feet tall and twice as wide, multiple-trunked and highly ramified. Occasionally single-trunked trees, which are rare, were seen. In Kokufu book 80, about six years ago, two Chojubai won Kokufu prizes. Two years later in book 82 another won. Chojubai had come of age.

Most Chojubai are enjoyed out of leaf, although the small glossy leaves are perfectly in scale. As Chojubai often flowers nearly year-round there is nothing stopping you from putting them on the display tables any day of the year. 30 cm

You might wonder why I put this in…Well, it is a Chojubai accent plant in the Kokufu show 40 years ago. Interesting, isn’t it, how tastes and techniques have changed? These days, this tree would be unlikely to even get accepted into a local Western show.

The vast majority of Chojubai grown for bonsai are the red-flowered variety; all the other photos in this gallery are of red-flowered trees. This is a white-flowered tree and it won a Kokufu prize. Very hard to ramify the white ones. 33 cm

Chojubai’s ease of ramification is enhanced with training, creating dense forms of intense complexity. Most unique to the Chojubai is the natural eccentricity and unexpected angles and directions in the branching, which are usually encouraged as they represent the special flavor of this variety. If this were a plant trained by music, that music would be jazz.

A red-flowered Kokufu prize winner. Very old. This is a good example of the extremes in technique used to create a very crystalized form. Impressive, and yet in some ways perhaps not showing the best of what Chojubai offers. Hmm, I wonder how long I will be in purgatory for that comment… 35 cm

One of the rarer single-trunked Chojubai. Another Kokufu prize winner. If you have a single-trunked tree, be very sure to cut all suckers that come from the root base. Beautiful old tree! The warty bark is evident only with great age. 38 cm

If you have a Chojubai, you’re lucky. Keep it moist. Plant in deeper containers to hold more water. If you have a young plant, put it in a big training pot with large size soil mix for a few years, so you have some energy to manipulate. Keep in the sun. Use a pesticide when shoots are elongating to control aphids. Wire main branches and shoots from the base for multiple trunks, and cut and grow following that. This is not so much to create branch taper, as there will be little of that, but for the short, zigzagging and erratic branching that is only created by many years of scissor work. Cut back in June to one to three internodes only on refined trees, leave extensions on younger plants to develop trunk. Always immediately remove shoots that come from the base that you are not intending to use as trunks—they will weaken the older areas. There’s more to it, but that will get you started.

Lovely loosely styled multiple-trunk Chojubai. Many years of careful scissor pruning created this natural form. 40 cm

Chojubai at my place in mid-December, showing tiny flower buds. Any strong tree, with timely trimming, will produce this many buds. It has already had a few flowers open, which are about 1″ across, and will continue blooming for 3-4 months until late March when the leaves start coming out. After that the blooming is more sporadic.

After all those words and photos, there’s no hiding that I’m totally besotted with Chojubai. Ah well. Another personal secret offered to the globe. But I have a wondering curiosity if these images stirred—if any photograph CAN stir—the endearments that Chojubai have raised in myself and others lucky enough to have seen them in person. I imagine many of you have never seen Chojubai before. What do you think? Something you’d like to see more of?